covers

One of the things I appreciate most about my publisher Jericho Books (an imprint of Hachette Book Group), is that they included me in a lot of the book-making process, which was much more arduous than I’d expected. Designing the actual physical book made the writing of the manuscript seem like the easy part.

The biggest decision in the whole process was not the font or the dimensions or the quality of the paper, but the cover design.

I named the book The Invisible Girls, which described both my experience of being lost after nearly dying of cancer, as well as the experience of the Somali mom and her five daughters who were swallowed up in a western culture they didn’t understand.

As the design team planned the book cover, they threw out a few ideas. First, they asked if they could put a picture of me on the front.

“No,” I replied to their e-mail. “Because the book is not just my story; it’s also the story of the Somali girls.”

Then they sent me a sidelit picture of an African girl, from their stock photography files. “No,” I said again. “Because the book is not just about an African girl; it’s also a book about me.”

After going back and forth, I finally suggested that there be no human element on the cover, since neither a Caucasian girl nor an African girl were representative of the book.

So the design team came up with the hardback cover, which is a blurred picture of the MAX train in Portland where I first encountered the Somali family.

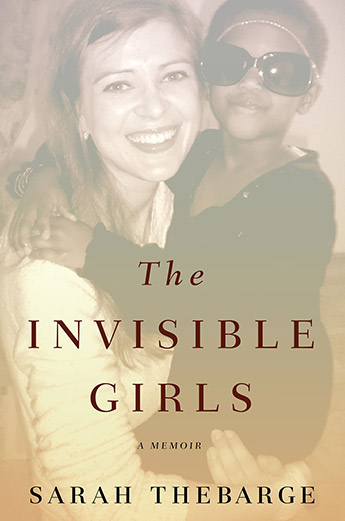

Before the paperback book launched this spring, there was another conversation about the cover. This time, the design team pushed for a picture of me with the Somali girls.

The idea was good in theory, but I was reticent to publish any pictures of them, since it was my idea (not theirs) to write a book about them, and because what good has it ever done any child to be thrust into the public spotlight at an early age? (No offense, Jason Bateman and Jodie Foster, but most of your compadres haven’t fared so well.)

Anyway. In the end, I agreed with them that a cover with a human element would be more compelling and descriptive than a picture of a train, so I sent them a few photos that I’d taken of me and the girls, asking the designers to either blur out their faces, or to use the photo of me holding the smallest girl, whose face was half-hidden by my diva-style stunner shades.

They chose that photo, and it’s on the cover of the paperback version of the book.

A few weeks before the paperback version launched, I got a box of complimentery books in the mail from the publisher. I picked one up and studied the picture, laughing at the memory of the afternoon that picture had been taken.

I’d driven from Portland to Seattle with a friend, and we’d taken the girls their favorite meal, which consisted of pizza, Sunny-D, Clementine oranges and ice cream. After I’d cleaned up the kitchen, I came around the corner to the living room, to find that the littlest girl, Chaki, had raided my purse to see what other surprises I had in my “pok-pok,” as she called it. She’d found my sun glasses and strutted around the living room, with her older sisters in hysterics.

One of them had grabbed my camera and snapped that photo of us.

As I studied the cover, I remembered the reason I’d taken a friend with me on that trip was because the day before I’d gotten an infusion of an anti-cancer drug, which always left me fatigued and achy for a week or two. I asked my friend to come with me so she could drive if I felt ill.

I remembered that the reason I’d met this family in Portland was because I’d had breast cancer on the east coast and after my life fell apart there, I’d sold everything I had and ended up on the west coast with just a suitcase of clothes. And that’s when I’d met this family -- who’d also escaped death and ended up with just the clothes on their back in a new place, learning how to start over, and nearly freezing and starving to death in the process.

Instead of being a death sentence, my cancer had been a catalyst that ignited a series of events that led to our paths crossing on a train in Portland.

I keep a copy of the book on my night stand. My favorite detail of the picture is not my smile, or the littlest girls’ grin, or the oversized sunglasses on her face -- it’s the bandage on my right hand, where I’d gotten the chemo infusion the day before.

The picture reminds me to pray for the girls every night before I go to sleep. And it also reminds me that sometimes my ends are God’s beginnings, that complications can be catalysts, that love transcends loss.

And that redemption comes at the most unusual times, in the most unexpected places.