day three in the dominican republic: lo siento

When we got to the barrio of El Cercado, a small village in the mountains of western Dominican Republic, Pastor Enal, Chris and I set out to do home visits for people who were too elderly, too sick or too frail to make it to the clinic the rest of the team was operating at a schoolhouse up the hill. The three of us walked about a kilometer down a dusty, unpaved road until we came to a one-room house built of concrete blocks that had been painted bright yellow. The house was surrounded by a 4-foot tall concrete wall, and a large banana tree provided shade to the narrow front yard, where an elderly woman was sitting in a plastic chair.

Pastor Enal knocked on the front gate, and asked the woman if we could come in. She nodded eagerly, undid the latch to the gate, and then disappeared to the back of the house.

We unstacked plastic chairs and set them in a circle. When the woman returned, her arms were heaped with what looked like unripe oranges, which she'd picked from a tree in the back yard. She gave us each a few of them, explaining that they were limon dulce, or "sweet lemons," a fruit I'd never heard of.

She handed Pastor Enal a sharp knife, and he made quick work of slicing off each end, and then cutting off the peel. We each did the same, and then began eating juicy wedges of the fruit which was exactly as the name suggested -- a slightly-sweet, round lemon.

As we ate, Pastor Enal asked the woman more about her story. She explained that she'd been married for nearly 50 years. Her husband was diabetic, and was currently in a hospital about an hour away. He had large sores on one of his legs -- a complication of diabetes, which causes diminished circulation to the limbs -- and the doctors were recommending an amputation.

But in the DR, most people don't have health insurance, and pay for their medical expenses out of pocket. The total for his surgery would be 300,000 pesos. I quickly opened the calculator app on my phone and did the math. It's 46 pesos to the dollar. So the man's surgery would coast $6,300 USD.

"Lo siento," I said, which means, I'm sorry.

"Even in the U.S., most of us couldn't afford that either," I said, and Chris nodded her head emphatically.

Government-run hospitals in the DR provide a bed and an IV for free. But you have to pay in cash for any other medications, procedures or surgeries before you receive them.

So the man was lingering in the hospital, receiving an I.V. and insulin, unable to get the amputation that would prevent him from getting gangrene and sepsis, and allow him to come home to his family.

Then the woman began to talk about herself. She retrieved a few bottles of pills from inside -- medicine she'd been prescribed but had run out of.

I listened to her heart and lungs, took her blood pressure and used the glucometer to check her blood sugar. Her blood pressure was high, but otherwise, the rest of her exam was normal.

We prayed with the woman, and then we left, promising to return that afternoon with enough blood pressure medicine for her to take until she was able to visit her doctor in a clinic a few towns over.

Next, we visited the home of an 80-year-old man whose 30-something-year-old son answered the door. He led us through a cool, dark, windowless front room to a small bedroom where a thin, elderly man lay in a sunken mattress on the floor, his head propped up with yellowed pillows.

The elderly man explained to Pastor Enal that eight months ago, he had suddenly become unable to use his left leg. He hadn't had a headache, blurred vision, dizziness, or any other symptoms. He'd just woken up one day and his left leg had been useless since. He pointed to a rough-hewn wooden crutch leaning against the wall next to his bed, and said he'd been using the crutch to get around.

"Do you have medicine for him?" his son asked me.

I sat on the edge of the bed, took the man's vitals, and performed a detailed exam. I concluded that the man had probably had a stroke eight months back. He didn't have high blood pressure, and his heart rate was normal so he didn't have atrial fibrillation. Other than a baby aspirin to prevent cardiovascular disease, and a multivitamin to supplement his nutrition, there was nothing to do.

"Lo siento," I said for the second time that day, as I broke the news to the man and his son that his left leg was permanently paralyzed, and there was no medicine to bring the function back.

We went several houses down and knocked on the door of a one-room wooden structure that, with the large spaces between slats of wood along the walls, and the sheets of corrugated tin that didn't quite reach the edges of the roof, was more of a temporary shelter than a house.

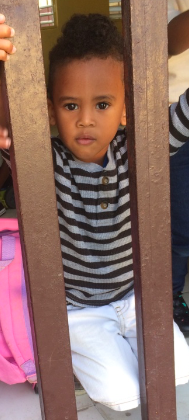

A young woman answered, and a toddler peeked at us from behind her legs.

Pastor Enal conversed with her for a minute in a language I didn't recognize. It wasn't Spanish and it wasn't French. "Creole," he explained.

The woman and her husband, as well as her brother and his sister, were refugees from Haiti who had arrived in the DR five months before. A wooden shed, a cluster of banana trees, some stray chickens and a patch of dirt comprised the back yard, where we sat in overturned buckets as the woman told us more about her story.

When she was 14, both of her parents died, leaving her an orphan. She had no one to pay for her to go to school, and felt that she had nothing left to live for, so she became sexually active (she didn't go into details, but from the context it seemed that she began to support herself by becoming a prostitute). When she was 16, she married the man who was now her husband, and gave birth to her son, Matti, who was now two years old. And now, she was 3 months pregnant with her second child.

With her permission, I examined her, her son, her 13-year-old brother, and her 14-year-old sister-in-law. I discovered that, while they spoke little Spanish, the each understood French -- which I speak. So I was able to communicate relatively well with them.

She wasn't taking a PreNatal vitamin. Her brother had asthma, but didn't have an inhaler, and was actively wheezing when I listened to his lungs. He had also had abdominal pain and cramping for the past six months.

I asked how many servings of fruits and vegetables he ate each day, and he looked puzzled -- not because he didn't understand the question, but because the idea of having multiple servings of produce a day was foreign to him.

"We eat whatever we can get," his sister said, adding that often their only intake of the day was a cup of rice, or an unripe banana.

I wrote her a prescription for a PreNatal vitamin, and I wrote her brother a prescription for an inhaler, an anti-parasitic for his intestines, and a multivitamin, since they had such limited access to nutritious food. I asked them to come to the clinic in a few hours so we could give them their meds.

Later, when they arrived at the school house to get their meds, I discovered that there aren't asthma inhalers in the DR. Instead, we had a nebulizer machine, so we were able to administer the 13-year-old one breathing treatment to clear up his wheezing for a few hours, though I was certain that the next day, the wheezing would be back again. I counseled his sister to take him to the hospital immediately if he felt like he couldn't breathe.

"Lo siento," I said, as I emerged from the pharmacy unable to provide him with an inhaler.

As I watched them slowly make the walk downhill toward their home, holding small paper bags with two months' worth of vitamins, I thought about my medical practice in the U.S., the many times I counsel patients with obesity or diabetes or high blood pressure or high cholesterol to eat more fruits and vegetables, and eat less processed/fatty/salty food.

And often, patients didn't comply -- not because they couldn't afford a bag of frozen spinach or because they didn't have access to blueberries, but because they choose not to, assuming that if their health continued to deteriorate, they would simply take more pills to counteract the effects of their poor dietary choices.

I have also taken care of asthmatics in the U.S. who let their prescriptions lapse -- not because they can't afford the medication, but because they simply choose not to make time to go to the pharmacy.

Having the ability to choose not to be healthy is much different from so many people in the developing world who can't eat healthy, and can't take the medicines they need, not matter how much they want to.

What do we do for them? I wondered, as we packed up the clinic bags and prepared to drive back to San Juan.

What do we do about us?

And what does it take for us to go from sientos to solutions?